The report suggested that not only would our longest serving British monarch be dropped from history lessons, so would other stalwarts of her era, such as Florence Nightingale, Mary Seacole, Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Alexander Graham Bell. Strongly denied by the DfE, the report prompted me to think of the winners and losers of our history curriculum, and why certain individuals are recalled far more than others.

The report suggested that not only would our longest serving British monarch be dropped from history lessons, so would other stalwarts of her era, such as Florence Nightingale, Mary Seacole, Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Alexander Graham Bell. Strongly denied by the DfE, the report prompted me to think of the winners and losers of our history curriculum, and why certain individuals are recalled far more than others.

As well as the obvious academic benefits, imbuing a sense of history in our youngsters provides one of the bonds that holds our society together. Henry VIII, Winston Churchill and Nelson have long been central figures in our education, as has Elizabeth I – the level of attention given to these individuals in education, academia and indeed popular culture can often verge on obsession.

But wherever there are winners there must also be losers, and despite being revered during their lifetimes and long after their deaths some formally significant figures are now completely absent from most schooling.

How many of us are familiar with Henry Havelock, for example? To remind you, he was of course a military leader whose heroics during the 1857 Indian Rebellion earned him the honour of one of four plinths on Trafalgar Square – he enjoys a commanding view of the tourists and pigeons to this day.

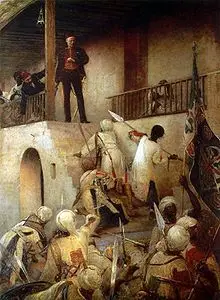

General Gordon, another stalwart of the Victorian era, whose last stand at Khartoum in the Sudan was celebrated as one of the defining acts of Empire, is another former national hero who has been largely forgotten. Indeed, the soldiers of Empire have long been absent from the school curriculum replaced by their less militant peers. Writing in the Evening Standard yesterday Richard Godwin suggested that some of our imperial leaders have been largely erased from the nation’s textbooks. As the sunset on Britain’s imperial adventure, so it set on the celebration of imperial heroes, with society increasingly uneasy about our past colonial conquests.

But perhaps it is better to pass anonymously into the dusty shelves of the history sections of the nation’s libraries, than to be almost universally despised. The consensus on Richard III, for example, is that he was a scheming child killer. However, the recent discovery of his skeleton under a car park in Leicester has prompted a re-examination of his legacy, with members of the Richard III society mounting a vigorous defence on national television. Yesterday a campaign was launched to see him buried alongside other monarchs at Westminster Abbey with a full state funeral.

Given the limits of the school curriculum there will always be winners and losers in what can actually fit into the school day. But perhaps a reshuffle of the history curriculum would not be a bad thing – it could offer an opportunity to re-examine the past’s leading men and women. Who is to say, for example that a study in Nelson is more worthy than a study in Henry Havelock? This is just one of the great education debates which continue to rumble on.