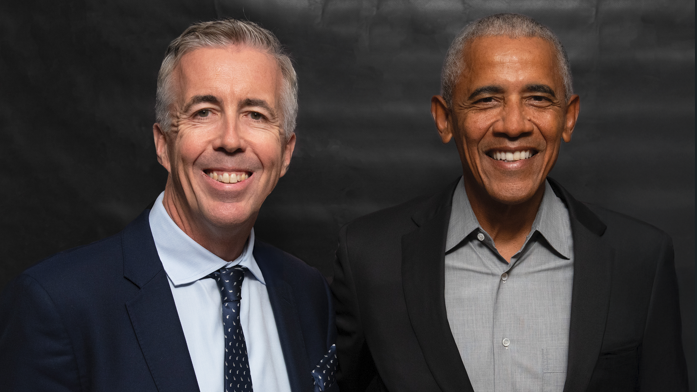

PLMR’s CEO and Founder, Kevin Craig, met the 44th President of the United States, Barack Obama, in London last week. Kevin and President Obama spoke about the importance of family and Kevin thanked the President for being an ongoing force for good in the world.

You can read Kevin’s reflections on his meeting with Barack Obama below.

They say never meet your heroes, but I have to disagree. Last week in London I met President Barack Obama. He radiated charisma, charm and patience to all the many people he encountered. I especially appreciated how kind and attentive he was when he met my two daughters, “daughters are the best,” he said to me, and I had to agree with him.

So, he was a delight to meet. But what about what he said in his speech?

Significantly, the 2025 Labour Party Conference showed that the Labour Party, fresh from a brilliant Keir Starmer speech in Liverpool, is already taking note of one of Obama’s big themes of the night in London: that for progressives to prevail, we must tell stories that move and connect.

Let’s be clear. Lincoln aside, Obama is the most significant President in modern US history. At one point, as he said himself, he was the most photographed person on the planet. The first digital US President. The first Black President. Looking younger than his 64 years, he had the audience at London’s O2 eating out of his hand. I thanked him for being a relentless force for good in the world and I hope he knows how many people are behind his ongoing work.

President Obama delivered a sermon in beautiful, measured prose. Less politician, more preacher, his post-Presidency work now tours the liberal world with a homily about democracy, equality and grace towards our political opponents. His main theme in London was the fragility of liberalism and the need to communicate it not just as a system of rules but as a story. To reach and move people, to ignite passion.

Much of what he said was familiar. Globalisation has winners and losers. The wealth it generated was immense, but it came with inequality and insecurity. Britain has lived through the same story as the USA. Entire regions of the UK feel untethered. Our old industries gone, our communities hollowed out. Populism exploits resentment. Institutions creak under the strain of 21st-century challenges. The relentless 24-hour social media landscape rewards outrage. Artificial intelligence looms. MAGA in the USA and Reform here are flourishing where economies are not delivering. Ultimately, truth is suffering.

He framed liberal democracy as a noble, if imperfect, experiment that deserves reverence rather than embarrassment. He urged progressives to temper impatience with those who have not yet absorbed what the Left so often conveys as obvious and self-evident. He pleaded for grace in political debate something too often forgotten.

President Obama said that given these challenges, progressives too often fail to articulate their cause with sufficient impact. Much of Starmer’s first year nodded to this – prose stripped of poetry. A Labour leader who talked solely of industrial strategy and green jobs risked sounding like a policy manual, not a visionary leader.

What was missing was the emotional register. The promise of dignity, fairness, and national renewal. The connection.

Starmer’s cannot be accused of a lack of competence. Far from it. Too often in his first year, this seriousness and capability, the sense of him being a man who can draft a contract, chair a meeting, audit a set of accounts, convene a table of strong leaders, has simply not cut through. The stories, the connection to voters, have been absent.

Labour’s most successful leaders understood the need to paint on a big canvas. Clement Attlee, the least messianic of leaders, did not win in 1945 by promising only clean government after Churchill’s turmoil. He offered a transformative vision of security “from cradle to grave” and linked it to the moral experience of wartime sacrifice. Tony Blair, for all his polish, won in 1997 by projecting optimism, suggesting Britain’s best days lay ahead, not behind. And in the United States, Joe Biden, whose charisma differs from Obama’s, nonetheless made 2020 a contest of stories – Trump’s zero-sum fear against his own “battle for the soul of America.”

Until Tuesday’s speech in Liverpool, Keir Starmer too often sounded like a man in front of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, footnoting his promises with actuarial caveats. Yes, voters want reassurance that the sums add up, but they also want something more elemental. They want a sense of belonging, a reason to believe politics sees them as more than units of revenue and expenditure.

Obama’s London lecture pointed towards that other half of the task. He described the clash between two stories of humanity. One of equality and trust, the other of hierarchy and fear. People harbour both stories within them. The question is which one politics dignifies. The nationalist right flatters instinct. The liberal left too often scolds it. The result is a lopsided contest.

Here, the lesson for Labour is clear. A politics that regards provincial conservatism as moral delinquency is doomed to fail. Blair understood this better than anyone. His was a politics of inclusion – bringing Essex Man and Mondeo Man into the Labour tent, not by berating them but by respecting them. Obama’s language of grace, of inviting sceptics in rather than excluding them, is the modern equivalent. Stop shouting at your opponents, he was saying.

In our democracies, rhetoric is the currency of power. Obama knew it. Reagan knew it. Blair knew it. Even Boris Johnson, for all his unseriousness, understood that optimism can trump detail. The case against the government is currently well made. The case for Labour is less vivid so far. Crucially, I see evidence of that changing in Liverpool.

Obama’s gift is to make liberalism feel romantic. He invokes the long arc of history, the sacrifices that gave birth to institutions, the sense that democracy is a fragile inheritance worth defending. He does it without self-pity and without sneer. Our Prime Minister does not need to become Obama. Britain is not America; our political culture punishes grandiloquence. Attlee’s understatement and Blair’s conversational modernity are closer models. But all three men understood that management must be embedded in a wider sense of mission.

Obama’s London speech a welcome reminder of politics’ oldest truth – people need stories. Starmer has one, of patriotic renewal after national decline, about fairness after years of drift. Until Tuesday in Liverpool he could be accused of whispering it. Not now.

It is an odd thought, but the fate of British politics may depend on whether a former American president has reminded our Prime Minister that he must be a better storyteller. When I watched Keir Starmer speak in Liverpool, I thought he was already showing signs of understanding the power of stories that inspire and move. Long may it continue.